Pictorialism in Context

Gertrude Käsebier's growing fascination with photography transformed her life as she applied her classical art training to the new medium in the 1890s. Her Pratt instructors attempted to dissuade Käsebier from pursuing her interest in photography-even from taking a camera to Europe in the summer of 1894—but each successful photograph reinforced her desire to continue. By 1898, she was one of the forerunners in the American pictorialist movement, and was gaining both national and international fame for her photographs.

Pictorialism, or art photography, was a growing movement in 1890s America, especially in cities with established photographic communities like New York, Boston, Philadelphia, and Washington, D.C. For more than a decade, photographers in England and Europe had been pursuing new techniques and processes to lift photography to the status of fine art. Soft focus was a predominant characteristic of pictorialism. Other qualities, including texture, "sketchy" effects, and range of colors and tones, were frequently used to obtain the desired painterly look in the photographic prints. Darkroom printing, especially the platinum process with its rich, dark tones of black and gray, or the manipulated brush-stroked textured look of the gum-bichromate process, were preferred by many of the pictorialists. (The Platinotype Process" 1899, 319-322)

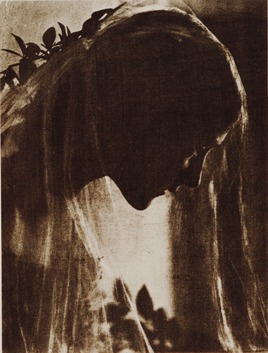

Adoration, 1898. By Gertrude Käsebier. Photographic History Collection, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution.

Even when the hand-held Kodak camera was introduced in 1888 by George Eastman, pictorialists remained dedicated to their bulky wooden view cameras on tripods. They resisted Eastman's film camera and company processing of film, continuing to use the older-style cameras and to develop glass plate negatives in their own darkrooms. Fortunately, the pictorialists, mostly serious amateurs, were generally a wealthier group with the resources and time available for the relatively expensive hobby.

Professionals, like Käsebier, and amateur pictorialist photographers formed camera clubs to focus more attention on the topic of photography as fine art. Through the active support of club leader Alfred Stieglitz, and members Edward Steichen and Käsebier, the Camera Club of New York, and later their Photo-Secession group (1902), became dominant forces in American photography. Stieglitz coordinated the work of the Club organizing exhibitions and publishing journals to further the national debate of photography as art. Stieglitz's exhibition galleries and publications promoted a select group of art photographers and contemporary artists. The small group of New York and American photographers working with Stieglitz included Käsebier, who was also recognized by her peers as a leader who established the standard for artistic portraiture in America.

"The American School" of photography was the subject of many articles written for the English journal Photograms of the Year by photographer Joseph T. Keiley, a New York contemporary of Käsebier and Stieglitz. For Keiley and other critics writing at the time, the years 1898 and 1899 were the most important for the beginnings of art photography in America. Gertrude Käsebier's developing career paralleled and influenced this movement, primarily centered along the nation's eastern seaboard. Exhibitions and salons highlighting the work of a small minority of photographers experimenting in pictorialism were critiqued and dissected in the amateur photography journals. The Philadelphia Salon of 1898 was the first photography exhibition to attain the professional standard set in Europe. Käsebier's photography was prominent among the works selected for the showing, second in number of entries only to her friend and New York colleague, Alfred Stieglitz. Her teacher, Arthur Dow, commented,

Mrs. Käsebier is answering the question whether the camera can be substituted for the palette. She looks for some special evidence of personality in the sitter, some line, some silhouette, some expression or movement; she searches for character and beauty in the sitter. Then she endeavors to give the best presention (sic) by the pose, the lighting and the focusing (sic), the developing, the printing-all the processes and manipulation of her art which she knows so well. She is not dependent upon an elaborate outfit, but gets her effects with a common tripod camera, in a plain room, with ordinary light and quiet furnishing. (Keiley 1899, 22)

This description led Keiley to comment in his review that

Mrs. Käsebier, who is a professional photographer, has quickly won for herself the position of the first portrait photographer in America. An artist by training and instinct, she has brought to her art that knowledge and feeling essential to the creation of good work, and there is no better sign of the changes in the public taste in such matters than the ever-increasing number of artists who are seriously turning to photography.(Keiley 1899, 22)

The New York Camera Club responded later in 1898, and again in 1899, with exhibitions under the leadership of Alfred Stieglitz, who continued his support of Käsebier's art photography and portraiture.

When the 1899 Philadelphia Salon was being organized, Käsebier and Clarence H. White of Newark, Ohio, were selected by the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts to serve as jurors. The Photographic Society of Philadelphia selected the remaining three jurors: Miss Frances Benjamin Johnston, Washington, D.C.; F. Holland Day, Boston, Mass.; and Henry Troth of Philadelphia. The group was charged with selecting photographs of a "class of which there is a distinctive evidence of individual artistic feeling and execution." (Keiley 1899, 22) In all, 954 photographs were submitted. Of these, 772 were rejected. All five judges received ample space for display of their own best work. Käsebier's photograph, The Manger, was among the most popular images shown in the salon, and established a sales record of $100 for a pictorial photograph. (Keiley 1899, 18-22)

The Bride, 1905. By Gertrude Käsebier. Photographic History Collection, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution.

Käsebier worked with her sitters like a painter, as she had been trained at Brooklyn's Pratt Institute. She studied each sitter, taking much care and time to pose them. Normally her portrait sessions could last hours with one individual. She used older equipment, a large wooden view camera on a stand for portraits, probably a Century camera. Instead of using faster modern mounted automatic shutters, she continued to remove the lens cap and count three to five seconds, usually, for the exposures on glass plate negatives 6 1/2"x8 1/2," and sometimes larger. (Homer 1979, 15-16, 32) Harriet Hibbard, Käsebier's assistant for more than five years at the studio acknowledged Käsebier as quite productive. Käsebier was reluctant to retouch any photograph, but printed as many as a dozen images in the darkroom to achieve what she deemed perfection. The photographer's granddaughter, Elizabeth O'Malley, recalled "above all else, [Käsebier] has sought to give those she photographed, the best of themselves," in typical motherly fashion. (Gertrude Käsebier Papers, University of Delaware Library)

Popular American and European photographic journals of the time ran articles sharing technical advice and aesthetic considerations that read as an homage to Käsebier, as her technique and skill established her as the leading American portraitist of her time. Despite limited training in photography, even her earliest prints proved elegant and graceful likenesses. The pose of each sitter, the composition and arrangement of space, were seen as vital to the success of each photograph. Käsebier's professional work habits and style reflected her own femininity and nineteenth century upbringing. She nurtured her sitters in conversation as best she could, to create a comfort level, while intuitively attempting to convey a provocative portrait true to their character and life.

Käsebier's appreciation of European Old Masters influenced her portrait work, but she subordinated poses and accessories, using tone and lighting to avoid self-conscious, rigid portraits. Decisions on the point of view of each image, and the positioning of the camera, were crucial. Journal articles suggested fixing the camera lens level with the sitter's mouth or chin. Käsebier explored the use of all formats: bust portraits, half, three-quarters, full-length, standing, seated, and group images. Her photographs often illustrated journal and magazine articles as the best examples of artistic portraits being made. Fashionable posing styles for men, women, children and groups, were explained, and problems to avoid described. Käsebier and other portrait photographers of her day were encouraged to develop "the cultivation of instinct," or the "continual observation of what is interesting and what has grace or beauty in nature and art as we see them in everyday life. . . that sympathetic interpretation which compels at once our interest and admiration." (Homer 1979, 81-82) Käsebier's striking platinum photographs in strong tones of black or brown, and her painterly textured gum-bichromate portrait photographs, and those of her close friends and/or contemporaries Frances Benjamin Johnston, Zaida Ben-Yusuf, Mathilde Weil, and Clarence H. White, continued to be reproduced as photogravure prints illustrating articles in leading photography magazines and journals.

It is within this context that Käsebier photographed members of William "Buffalo Bill" Cody's performance troupe. An archive of articles provided here document Käsebier's unique position in society as a photographer and provide a context for her work by demonstrating how she was received by her contemporaries.