The 1898 Season

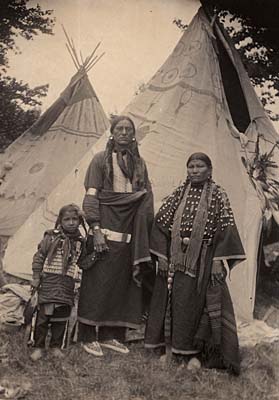

Spotted Tail and his Family. By Gertrude Käsebier. Photographic History Collection, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution.

William "Buffalo Bill" Cody relied heavily on Native American participants for the success of his show. Tribal chiefs were often reluctant to let their people go, but Buffalo Bill and John M. Burke, Wild West manager, proved persuasive in most cases. (Moses 1996, 26) The federal contract stipulated that the Indians must "obey orders, refrain from all drinking, gambling and fighting." Burke organized Buffalo Bill's Indian Police. The number of Indian "policemen" was chosen depending on the number of Indians traveling with the show each season, a usual ratio being one policeman for every dozen Indians. In any given season of the Wild West, Indian performers normally ranged in number from 100 to 200. Indian policemen, elected from within the ranks of Indian performers, were given badges and paid $10.00 more in wages per month. ("Indians in the Wild West Show: Even When Not Performing They Wear Native Dress," 1901) Chiefs Iron Tail and Short Man were leaders of the Indian police in 1898.

Today, Buffalo Bill Cody's scrapbooks of newspaper clippings from virtually every city visited on the Wild West yearly program provide invaluable references to scholars. Whether in New York, Chicago, or Kansas City, publicists for the show supplied local journalists with updates on the program, and the year's highlights. The 1898 season, corresponding with the making of Gertrude Käsebier's first portraits, was the first to include the Cuban Rough Riders, wounded freedom fighters on furlough awaiting return to battle the Spanish. Their story and their horsemanship rivaled that of the American Indians in popularity with the audience. Many articles in the 1898 scrapbook reference Buffalo Bill's readiness to join the American forces fighting the Spanish-American War as a scout for the Army. He boasts in one article for The World, April 3, 1898, "How I Could Drive the Spaniards From Cuba with 30,000 Indian Braves," acknowledging his respect for Native American skills in warfare. (1898 Buffalo Bill Cody Scrapbook, McCracken Research Library)

Short Man. By Gertrude Käsebier. Photographic History Collection, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution.

The newspaper accounts of the 1898 season of Buffalo Bill's Wild West, much like other years, chronicles attendance logistics and interesting moments along the sixth month tour. Numerous reports focus on the Show Indians and their daily lives and activities while on tour. The New York Journal, April 17, 1898, one week prior to the Indians' visit to Käsebier's studio, announced their appearance in the annual Fifth Avenue Easter Parade, attracting attention in their colorful coats, feathers, blankets, and moccasins. The Baltimore News of May 12, 1898, ran a commentary, "How the Indians and Other People of the Show Live," reporting that "Indians consider it a great privilege to travel with the show and make money." The Indian Police force was described as keeping order among the warriors. Offenders, those who broke established rules, were sent back to the reservation, and another Indian sent as a replacement. Four women and two children traveled with the troupe in 1898. The "wigwam encampment" was set-up in back of the main tents and easily available to visitors. The Indians ate in the large dining tent, served the same food as other performers and workers but, curiously, no desserts, as was their stated preference. The press, like thousands of spectators to the show, was repeatedly fascinated with the apparent ease at which the Show Indians adapted to a theatrical life, and one so far from the Great Plains. (1898 Buffalo Bill Cody Scrapbook, McCracken Research Library)

It was during this season that Gertude Käsebier was fortunate enough to have nine Lakota men sit for her camera in her Brooklyn studio. This initial sitting led to many more portraits and long-lasting friends.