FREDERIC REMINGTON (1861-1909)

A note from Robert E. Bonner.

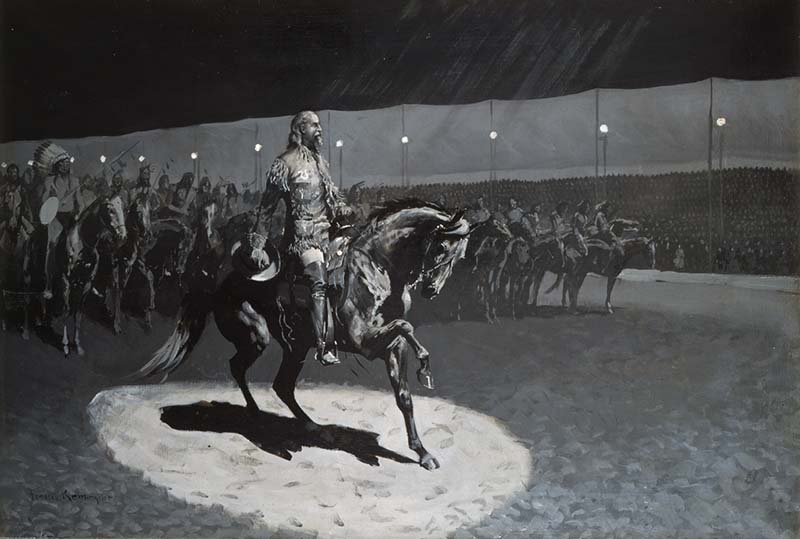

As with most of the artists he knew well, Bill Cody first met Frederic Remington on the grounds of the Wild West. They met in London in 1892, as the artist stopped there on the way home from an unpleasant tour of Europe. Though Remington had previously produced some illustrations for Cody's Story of the Wild West in 1888, they only became friends while Cody's show toured London. A further contract for illustrating an article and ten drawings in Harper's Weekly in September of the same year cemented their friendship and professional relationship. From that time on Remington was a frequent visitor to the Wild West, and an interpreter for the public of the civilizational meaning of Cody's arena production. Remington also illustrated Helen Cody Wetmore's adoring biography of her brother, one of which is a justly famous equestrian portrait of the old showman, In the Limelight. The publishers only printed these illustrations with the more expensive editions of the book, but Remington permitted Cody to use that portrait in post-1901 Wild West programs. Remington and Cody stayed on good terms, but they were never as close as Cody and other artists with whom he worked. Remington neither needed nor wanted a patron, and Buffalo Bill's public trajectory was similarly independent of anyone else. They could occasionally be useful to one another. [1]

Remington did not need Cody's patronage, but he did need to experience the West. Though he began his career as an illustrator in the southern and southwestern plains, he turned more frequently to the northern plains later in life. Remington and Cody arranged a visit to Cody's new little town in the Big Horn Basin for August 1899, when the artist was on one of his painting trips. Remington and his wife traveled first to the northern Wyoming ranch where Cody's daughter, Arta, and her husband, Horton Boal, lived. There they made up a traveling party with Arta, her sister, Irma, and her mother, Buffalo Bill's wife, Louisa. None of Cody's family had yet seen the Big Horn Basin, and they looked forward eagerly to the trip. George Beck, the managing partner at Cody, was to serve as host. He met them at the railhead in Red Lodge, Montana, fifty miles away, and brought them to the raw little town on August 3, where they stayed for nearly two weeks. Of course, Buffalo Bill was not there; he was traveling with the Wild West, but he was actively concerned that the trip be a success. He wrote Beck in mid-July, "Hope you will all have a nice time on the pleasure trip. Remember Remington has a mouth and likes his toddy–so stay with him. Gerrans says whiskey is the best." [2]

According to his host, Remington "did little or no work" on this visit to Cody. The trip focused more on the Cody women, and the Remingtons joined in the spirit of it. The most memorable day occurred when the citizens of Cody organized a picnic and dance at the Colonel's Carter Mountain ranch. The party, the invitation to which extended to the entire county, required a long ride up a rough trail to reach the cabin at Irma Lake. Remington never traveled without at least a sketching outfit. On this day trip he produced a pair of charming pen-and-ink drawings, one of Irma on horseback, Irma Going to Irma, and another of himself dancing with Louisa, The Big Things. There was not much time for dancing, as an afternoon rainstorm drove everyone into the cabin and spoiled the decorations on the pavilion, but everyone's spirits remained high. In fact, according to Buffalo Bill's daughters, high spirits marked the entire fortnight. [3]

Some other production emerged from this trip. He painted an oil sketch of an anonymous rancher and inscribed it "to Col. W. F. Cody, Big Horn Basin '99," no doubt a gift in response to Cody's hospitality. He also painted a simple oil of a pack horse for George Beck. A fine black-and-white oil of a group of cowboys gathered by a mail box on a sage-brush plain, without a date but ascribed to 1901, carries the notation "Big Horn Basin" by his signature. It is representative of the figurative, narrative style that made Remington famous, right down to the title, A Post Office in the "Cow Country". [4]

Remington's second visit to Cody, in the fall of 1908, was much more important, personally and artistically, though Buffalo Bill had nothing to do with this trip. Remington was at a creative tipping point as a painter, moving away from the kind of narrative figure painting that had been his ticket to success as an illustrator. Although figures remained at the center of his work, he was striving by 1905 or so to soften the hard-edged clarity of representation in his paintings, evolving a style that depended much more on color and tone. The New York Times reviewed his 1906 show at Knoedler's (the venue itself a significant step away from magazine publication, into the fine art world), saying that it looked as if he had been studying the "delicate aerial niceties" of European painters. Previously hostile to landscape art, he now produced it, and in early 1908 expressed a desire to get out in the sage brush of the Big Horn Basin. He was quite a different painter than the one who had traveled to Cody nine years earlier. [5]

A Post Office in Cow Country, 1901

Frederic Remington | Oil on Canvas

Buffalo Bill Center of the West

Arriving in Cody September 15, after a miserable, hot train ride from Chicago, George Beck once again met him on the platform. Beck already had a pack train ready for a hunting trip up the South Fork and over into Jackson's Hole. Although Remington originally wanted to go for only ten days or so, he accepted Beck's proposal for the longer trip but insisted that they go by way of Irma Lake, where he had been in 1899. He was determined to revisit the light and color he remembered there. Beck agreed, as this plan would allow Remington a few days to adjust to the altitude as he painted his way up river. The artist told his wife before they left that the trip might take a month, but it was probably his last chance, so he was going to take it. He was suffering from gout–he referred to himself as "a one-legged man"–and, weighing in the neighborhood of 300 lbs., was unable to sit a horse. His gargantuan appetites for food and drink still ruled him, in spite of frequent attempts to get on the water wagon. When they started their trip Beck sent the camp wranglers ahead, and he and Remington followed some hours later on a buckboard wagon. When they caught up with the camp staff, Remington insisted on stopping for a drink. They breached a five-gallon keg of whiskey and Remington drank down a cup of it raw. When they made camp he had another before dinner, and more after dinner as they sat around the campfire. He arose late the next morning complaining of not feeling well, saying he was not interested in breakfast. When the cook scrambled a couple dozen eggs with bacon he sniffed it and took a few bites on his plate, then asked for the skillet and ate it all down. The cook watched this performance, then asked Beck how much he would have to prepare when the painter was feeling like eating. [6]

The party stayed at Irma Lake a few days while Remington got down to the serious business of the trip. Beck has left an account of the painter at work:

He carried around a small smooth board with a hole cut in it for his thumb instead of a regular palette. His pockets would be bulging with tubes of color and he always had a huge fistful of brushes and pencils. After the scene was sketched he would daub a lot of primary colors on the board and, taking a brush, he'd mix a shade he wanted. Then, taking another brush, he'd dab spots of this color all over the canvas. Throwing that brush on the ground, he would take another and start on another color, repeating the process of putting it on in spots wherever the color hit his eye. Finally he would get so many bright daubs of paint on the canvas that it looked more like a sample of Joseph's coat of many colors than a picture. And then he would begin mixing some dark paint for the shadows. Once he had his shadows in, the picture suddenly stood out–completed. He did several landscapes of the Shoshone looking north, and even my old buckboard and wagons did their duty as models for future reference.

A dozen or more oil-on-board landscapes of views of the country around Irma Lake show the results of this technique and that short stay on Carter Mountain. Remington did not take much pleasure from the stay at Irma Lake. It was cold and windy, and sleeping on the ground was painful. He was having difficulty with the altitude. The night around the campfire may have been an exception: historian Brian Dippie identified it as the source of one of his finest late paintings, The Hunters' Supper, completed in 1909. [7]

When they moved upriver to Buffalo Bill's TE ranch, things did not improve very much. They arrived there to find close to forty pounds of trout, caught by a Cody doctor and a boy. Beck's cook got out two frying pans and proceeded to cook up the entire mess, as Remington and Dr. Ainsworth announced their intention to eat as many as they could. By the end of the evening all the fish were gone. Dr. Ainsworth was sick right after dinner, and Remington followed suit before bedtime. But he remained in some distress, pacing the bedroom floor for an hour, muttering, "By God, I'm going to die. I'm going to die this time." Then, "But I don't give a damn. They were worth it!" Beck and his party were ready to move on the next day, but Remington did not feel like going on, so Beck left a cook for him and headed off into the mountains. A few days after they left a storm blew down the canyon and Remington decided he had had enough. He and his companion returned to Cody on September 24, only eight days after he had left. By the time Beck returned to Cody Remington was in a warm, soft bed in St. Paul, on his way home to Eva. [8]

That week in Wyoming was difficult but very productive for Remington. Six, possibly eight, finished paintings and a large number of sketches and unfinished studies testify to his energy and determination to make the most of his last trip west. In addition to two night paintings, there were four small oil-on-board landscapes: Shoshonie, Top of the Big Horns, and two untitled, one of log ranch buildings and a wagon, the other of Carter Mountain. These reveal the artist as one "in search of the beautiful," as he described himself to Eva. And there is more. Hassrick asserts that Remington's purpose in his last decade was to search for the unity of man and nature. Certainly the centering of a pair of Indians in the landscape of Top of the Big Horns is a consummate example of such a union. One of the large canvases from this trip, finished in his studio in the summer of 1909, Buffalo Runners in the Big Horn Basin, approaches the same goal from a different direction. In this painting the action painter from his early days and the Impressionist he had become fuse to compelling effect. The riders, ostensibly the subject of the work, seem to emerge out of the ground in an explosion of high prairie colors–yellow ochres, browns, reds–in which the grass and horses and riders run together in a tumult of light. The genesis of the painting may perhaps be seen in an oil sketch from that trip, untitled but alternatively designated Ghost Riders. The fusion of that country and his memory elicited this last tribute to the energy of those horsemen he had once known. Remington had gone to Wyoming to find the light and to work with the color, and he succeeded dramatically. It is hard to escape the conclusion, however, that in spite of the cheery bonhomie of his farewell note to George Beck, he left Wyoming feeling the weight of his mortality. [9]

Log Ranch Buildings with Wagon, 1908

Frederic Remington | Oil on Board

Buffalo Bill Center of the West

So what of Bill Cody in all this? Cody never actually hosted Remington in Wyoming, as the Wild West was running somewhere else both times the painter visited. But the Cody-sponsored 1899 trip set a hook in Remington's artistic memory that led to the 1908 trip, and the work from that one week was arguably more important to the artistic legacy of Bill Cody than anything he did himself. What Buffalo Bill himself could not do, the country he chose as home may have done for him.

[1] Allen P. and Marilyn D. Splete, Frederic Remington—Selected Letters (New York, 1988), 80, 140; Frederic Remington, “Buffalo Bill in London,” Harper’s Weekly, Sept. 3, 1892; Helen Cody Wetmore, Last of the Great Scouts (Duluth, 1899), 243. In the Limelight is titled Buffalo Bill in the Limelight in the Whitney Gallery collection, object no. 23.71, Buffalo Bill Center of the West.

[2] Arta Boal to George Beck, June 14, 1899, Box 2, folder 2, George T. Beck Papers, Accession no. 59, American Heritage Center; Cody to Beck, July 18, 1899, letter no. 103, Buffalo Bill Cody letters to George Beck, Accession no. 9972, American Heritage Center.

[3] George T. Beck, “Beckoning Frontiers,” unpublished memoir, Book IV, 83, in George T. Beck collection, Park County Historical Society Archives, Cody, WY; unpublished memoir of C. E. Hayden, 14-15, Park County Historical Society Archives; Cody to Beck, Aug. 10, 1899, box 2, folder 2, Beck Papers, AHC. Buffalo Bill had named lakes on his Carter Mountain ranch after all the women in his family. The Big Things serves today as the emblem of the annual Patrons Ball at the Buffalo Bill Historical Center. At least one commentator has mistakenly identified the Irma sketch as going to the Irma Hotel, which was not yet built when Remington was there; it obviously refers to Irma Lake.

[4] Portrait of a Rancher, oil on board, in Buffalo Bill Museum and Grave, Golden, CO; Unhaltered Pack Horse, oil on canvas, Whitney Gallery, Buffalo bill Center of the West; A Post Office in the “Cow Country” , black and white oil on canvas, Whitney Gallery, Buffalo Bill Center of the West. The 1901 ascription and commentary for this last painting is from Peter Hassrick and Melissa Webster, Frederic Remington: A Catalogue Raisonne’, vol. 2, 735. It is not clear that Cody kept Portrait of a Rancher. It was never listed among his paintings in Cody; it was in the Buffalo Bill Museum and Grave collection at least from 1930 but there is no clear trail telling how it got there.

[5] Peggy and Harold Samuels, Frederic Remington; a Biography (New York, 1982), 363, 378, 386, 396, 402, 404; Peter Hassrick, "'That Hymn of Divine Crudeness,' Frederic Remington, the Painter," in Peter Hassrick and Melissa Webster, Frederic Remington: A Catalogue Raisonne’ of Paintings, Watercolors, and Drawings (Buffalo Bill Center of the West, 1996, 11-17. Brian Dippie has pointed out the similarities between Remington’s 1908 painting of his New York home, Endion, and Claude Monet’s 1894 painting of the cathedral at Rouen; Dippie, The Frederick Remington Art Museum Collection (New York, 2001), 197.

[6] Remington to Beck, Aug. 2 and Aug. 7, 1908, Frederic Remington Collection, MS 23, McCracken Library, Buffalo Bill Center of the West; Remington letters to his wife, Eva, September 13 and September 15, 1908, in Special Collections, Owen D. Young Library, St. Lawrence University, Canton, NY; Beck, "Beckoning Frontiers," 83-84; Dippie, The Frederic Remington Art Museum Collection, 206-208.

[7] Beck, "Beckoning Frontiers," 83-84. Landscapes that date from this trip in the Buffalo Bill Center of the West collection include one named painting, Shoshonie, Whitney Gallery ID 38.67, and a number of untitled ones carrying ID nos. 14.67, 22.67, 55.67, 59.67, 64.67, and 69.67. One of these, 14.67, provided the setting for his Top of the Big Horns; see Catalogue Raisonne’, 825. See also Dippie, Frederic Remington Art Museum Collection, 206.

[8] Beck, "Beckoning Frontiers," 86-87; Remington to Beck, [Sept. 24, 1908], MS 23, Buffalo Bill Center of the West; Frederic Remington, unpublished diary, September 1908, Frederic Remington Art Museum, Ogdensburg, NY. For what it is worth, Beck placed the trout event at another South Fork ranch, but Remington was emphatic in his diary that it was the TE, even to the point of insisting that he slept in Colonel Cody’s bed. Alexander Nemerov regards Remington’s overindulgence in food and alcohol as morbid, evidence of his preoccupation with his death, which in turn led him to represent in his later work "not the plenitude but the emptiness at the core of an object;" Nemerov, Frederic Remington and Turn-of-the-Century America, 145-149.

[9] Remington to Beck, [Sept. 24], 1908, box 6, MS 23, Frederic Remington Collection; Remington to Eva, Sept. 13, 1908; Hassrick, “’Hymn of Divine Crudeness,’” Catalogue Raissone’, 11-17. Hassrick discusses Buffalo Runners in the Big Horn Basin in his Frederic Remington: Paintings, Drawings, and Sculpture in the Amon Carter Museum and the Sid W. Richardson Foundation Collections (New York, 1973), 170-171. There was apparently another landscape painted from this trip, The Shadow of the Big Horns, which Remington sold but of which no image survives; Catalogue Raissone’, 834. The Catalogue Raisonne’ shows color plates of four paintings from this trip, nos. 97, 100, 102, and 105, among twelve paintings and studies attributable to his 1908 South Fork experience, pp. 824-852. It is perhaps worth noting that Remington called the mountains west of Cody the Big Horns. As far as we know, he did no painting in the range properly known as the Big Horn Mountains, on the eastern side of the Big Horn Basin.