CHARLES S. STOBIE (1845-1931)

A note from Robert E. Bonner.

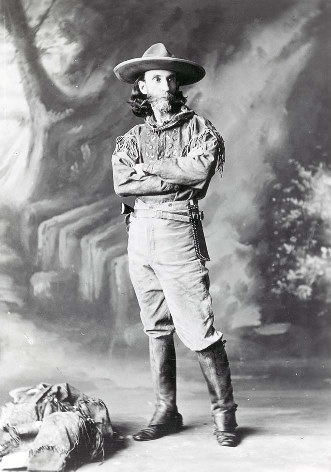

Charles S. Stobie, known familiarly around Colorado as "Mountain Charlie," or sometimes "Ute Charlie," from his long association with that tribe, was a friend of Bill Cody's from the 1860s onward. He moved West to record the life of western Indians after the Civil War, and already undertook some formal art study. He remained in Colorado, in the mountains and on the plains, performing occasionally as a scout for U.S. Army units, living and painting with the Utes, until he returned to Chicago in 1875 and set up a painting studio. Until the end of the century he moved back and forth between Chicago and Denver. We do not know exactly when Cody and Stobie met, but they were nearly the same age and traveled much of the same ground during the 1860s and 1870s. When Cody set out to commission a series of paintings of his fall hunting trips, he invited Stobie to join the 1902 party and produce a big oil painting to commemorate it. [1]

Cody opened his grand hotel, the Irma, in 1902. The entire hunting party, including Stobie, attended the night of November 18 for an extraordinary gala celebration. The next day they set off up the South Fork of the Shoshone River for Cody's TE ranch, a group of twelve men and 21 horses. The party included, besides Cody and Stobie, some of Cody's oldest friends–D. Frank Powell ("White Beaver"), Charley Christy, Mike Russell–at least three Indians–Sammy Lone Bear, Iron Tail, Two Bulls–plus one newspaper correspondent, Charles Wayland Towne of the Boston Herald, and a few men who worked for Cody. When they arrived at the hunting camp, about ten miles of high mountain trail above the TE, Stobie began to take pictures and make notes in a pocket sketch book. Stobie thought the camp, "Hidden Camp Bob," a beautiful location, overlooked by a high, precipitous mountain face and surrounded by a ring of tall pines behind the lodges. His notes included several sketches, with information on colors, and he painted an oil color study of the mountain above the camp. He repeatedly noted the brilliance of the sunlight on the snow, repeating also that the picture should be warm in its effect; "Keep Picture Warm" was his mantra. After five days in camp they rode back down to the TE, where Buffalo Bill gave him some pictures and a hat he had worn in the arena. Stobie presented Cody with a pen-and-ink sketch and received a $200 check for his expenses. Stobie went downriver first, but a few days later Cody caught up and they spent a night together at one of Cody's ranches close to town, where they "occupied the back room and slept together. Talked about old times and timers until late." They agreed that Stobie would send a painting to Buffalo Bill in London. [2]

Buffalo Bill left to begin his second European tour early in 1903. In March he wrote Stobie from London to confirm the picture's arrival. He had taken Irving R. Bacon's painting, The Life I Love, with him, to which he compared Stobie's work. Stobie's mountains and scenery he thought were "magnificent; at a glance it is by far the catchyest." But he thought the likenesses of the men were "very bad." And in spite of Stobie's warnings to himself to keep it warm, Cody thought the campsite looked "cold and uninviting." No detail was too small to escape the Colonel's attention: "Say, lots of people laugh at my foot. You have a number 12 boot on me. The position in the saddle great." No one liked Stobie's Indians, and some of the horses were out of proportion. Stobie had apparently said something to Cody about painting a larger canvas, so Cody advised him to take his time with it and pay special attention to the likenesses of the hunters. He also suggested that Stobie include some people tanning hides, repairing saddles, and performing other camp duties. He wanted to see a campfire to warm things, with some kettles on it as if they were going to have something to eat.

In a remarkable paragraph, Cody set forth what we might call his aesthetic of painting:

I think a painting should be made as true to life as possible for it to have true value, and the camp to look inviting, so one would say I would like to be there. This camp of your looks to [sic] cold not a fire in sight Indian women & children sitting around in the snow. I don't think there should be women and children and mongrel dogs on a hunt. I want the painting for myself to be as near true to nature as possible, so in after years I can say there is Charlie Christy or Gus Thompson or Roy Myers, and recognize them. I want a painting of myself and friends who were with me, to keep to remember the hunt. Work your own self in so I can say there is Charlie Stobie, the artist. Can you understand me? And I know what I want. Not an imaginary picture altogether, but parts.

In other words, Cody wanted his painting true to life, except where he didn't. As his Wild West improved upon the western history he had actually lived, so paintings of his life in the Wyoming mountains would conform to a higher standard of attractiveness. None of the sources for this hunt recorded whether Indian women and children were present, so we cannot know whether Stobie was faithfully recording what he saw or improving it in a different direction. In the large painting he completed later that year the Indian women and children disappeared, but there is still no campfire. The scene overall seems less wintry; the men may be more or less recognizable, but they are now arranged as if for a snapshot, and Cody's horse is simply standing, where before he had been dancing a bit. [3]

Cody closed his letter by asking the artist's pardon if he had been too critical, "but you want to please me in this big painting I feel sure, for you expect me to buy it, and I want it. But I want it to suit me, so I will be pleased with it." And he included a letter from Arthur Jule Goodman, who was painting his portrait for the Royal Academy, in which Goodman says that Cody's criticism improved the portrait; implicitly, he was challenging Stobie to respond as Goodman had done, while reminding him of the whip hand he still held over the transaction. There is some evidence that Buffalo Bill withheld payment, but as there are two paintings and he ended up with both of them, it is impossible to know. A friend of Stobie's, Mike Taguin, wrote him in 1904 to say he was sorry to hear that Cody had not paid him, "but since he serve [sic] me the same way I am not surprised." The first painting Cody kept with him and hung on the wall of his parlor at TE; it later became part of the Buffalo Bill Museum collection in Golden, CO. The second, larger canvas became part of the Irma Hotel collection and from there it migrated to the Buffalo Bill Center of the West. The only record of any payment is Stobie's note that he received $200 "for expenses." [4]

Cody's experience with Stobie was probably the least successful of his ventures with artists. Stobie never produced the kind of work Cody needed to represent his Wyoming life to a wider audience, and to generations yet to come. This did not put him off his tendency to rely upon people who had worked with him in the past, but he did turn to younger men to begin to capture his life and his legacy on canvas.

[1] Evelyn Rae Stool Waldron, "Charles S. Stobie: Mountain Charlie; Colorado Painter, Poet, and Mountain Man," unpublished paper for Department of History, University of Colorado-Denver, Spring 2008, 1-4.

[2] Memo and sketch book on trip to Wyoming, 1902, Charles S. Stobie Collection, Colorado Historical Society, MSS 609, ff 38; Charles Wayland Towne, "Preacher’s Son on the Loose with Buffalo Bill Cody," Montana; The Magazine of Western History, xviii, 4 (October, 1968), 40-55.

[3] Cody to Stobie, March 12, 1903, MS 126, ff 1, William F. Cody Collection, Colorado Historical Society.

[4] Cody to Stobie, March 12, 1903, and Mike Taguin to Stobie, April 7, 1904, MS 126, ff 1, William F. Cody Collection, CHS. Steve Friesen, Director of the Buffalo Bill Museum and Grave, Golden, CO, supplied some of the information used here.